Category Archives: H

Sterling Products, Inc. (VI.1.b.(2)) – AHP – Manhattan Medicine Co.

Sterling Products, Inc., Manufacturer

Chapter 6.1.b.(2): American Home Products –

Manhattan Medicine Co. – Manufacturer

JOHN F. HENRY “FACIMILE STAMPS”

Before folding into AHP, the Manhattan Medicine Co. (MMC) had its own long and colorful history. MMC’s principal bears a familiar name – John F. Henry (1834-1893) . Readers of the Wells Richardson & Co. column (Sterling Products, Inc. V.1.) will recall that Henry was the hard-charging entrepreneur from Vermont who succeeded Demas Barnes. Barnes was one of the earliest of the patent medicine millionaires who had built a multi-brand national empire just before the Civil War mostly wholesaling potions. In the period just after the Civil War, John F. Henry performed the same function, but with a great deal more emphasis on the retail than the wholesale side of the operation, gathering disparate nostrums into a single centralized mixed operation: in essence, doing what this chronicle is demonstrating AHP did in the retail market between fifty and sixty years later. With all these various medicines to juggle, Henry worked continuously and took chances, failing twice and reorganizing his business, once in 1878 and again in 1887. He also found time to cut a figure in Republican politics throughout the 1870s and 1880s, running and losing for mayor of Brooklyn in 1877 and losing later for a state senate seat as well. He was a prominent enough figure to be profiled in at least one of the Brooklyn civic puff books of the era. That he was a risk taker throughout his life is shown by the colossal size of the judgment entered against his estate in the amount of $382,974 in 1894 after a trial in which it was claimed that he had misappropriated funds as a trustee of the Widows & Orphans’ Benefit Life Insurance Company in 1871. While the trial court held against Henry’s estate, that verdict was never collected, however, because the defense primarily relied on the technical argument that the lawsuit seeking that recovery was not brought in timely fashion, and the highest court in the State of New York, the Court of Appeals, ultimately upheld that legal position in 1897.

JOHN F. HENRY PORTRAIT

While retaining a stake in the Vermont operations discussed in the Wells Richardson & Co. column, Henry plunged into his New York City ventures by re-styling the Demus Barnes operation as John F. Henry & Co. Concerning the number of products that Henry handled through that company, Holcombe writes: “It would be virtually an endless task to even list the many proprietaries which John F. Henry acquired…. Endless yes – impossible is the better word! The writer has listed well over a hundred and that list is nowhere near complete. Then too, Henry was ‘wholesale agent’ for as many more ….” Interested readers can pursue the philatelic ramification of Henry’s handiwork in Holcombe’s own book, but this article discusses one product that John F. Henry treated so specially that it quickly became the central focus of the new company, MMC, which Henry created in 1874 and for which he ordered private die proprietary stamps separate from those used by John F. Henry & Co.¹

MANHATTAN MEDICINE CO. PRIVATE DIE PROPRIETARY STAMPS

That product was Atwood’s Bitters, first marketed as Atwood’s Quinine Tonic Bitters and later sold under name variations such as Atwood’s Jaundice Bitters, a name familiar to every bottle collector in the world because of its great variety of shapes and labels which make collecting Atwood’s Bitters bottles seemingly a sub-specialty in itself. This article may help to explain why all these variations occurred, for while John Henry fought for MMC’s right to own and control Atwood’s Bitters entirely, the product had a long, elusive and disputed history that pre-dated his involvement by decades, absorbed his energy for years and out-lasted him by nearly again the length of his life.

1874 HALL’S JOURNAL OF HEALTH BITTERS RANKING

When generally discussing bitters, the starting point must be that a great deal of popularity of all bitters rested on the percentage of alcohol that they contained, for bitters were, even in that day, known and recognized in educated circles to be a coded term for booze. As an 1874 article in Hall’s Journal of Health ranking the potency of popular brands of bitters stated: “while persons are using Bitters as a medicine, and speak of taking ‘nothing but Bitters,’ they are often drinking three times a day a more concentrated form of Alcohol than is found in the purest Whiskies and Brandies…” However, immediately confusing any particular discussion of Atwood’s Bitters is that the article contained two different and separate listings for Atwood’s Bitters: a product called Atwood’s Bitters containing 26% alcohol that ranked fifteenth among thirty-four listed bitters, and another called Atwood’s Tonic Bitters containing 40% that ranked thirty-first among the listed thirty-four. That bitters contain alcohol reveals the reason for the intensity of the fight for Atwood’s Bitters, and that there were two different listings for those very Atwood’s Bitters demonstrates immediately the complexity of the dispute for their ownership and control that raged for forty years.

MOSES ATWOOD’S BITTERS

Atwood’s Bitters were first marketed in 1840 by one Moses Atwood of Georgetown, MA., a small town north of Boston and east of Lawrence. In his own article about MMC, Holcombe neatly traces the ownership of the Bitters from Atwood to a Vermonter named Alvah Littlefield, who first employed Demas Barnes and his successor Henry as distributors, and whose son allegedly sold the Bitters to Henry in 1877. Wrapping up his very short, tidy article, Holcombe finally noted that the Bitters, which were still being sold in 1935 by the Wyeth Chemical Co. as successors to MMC, still bore the facsimile image of John Henry. While virtually entirely incorrect, this narrative keeps the story Holcombe is telling very simple. Holcombe’s chose as his illustration for this article the facsimile “stamp”² that also appears at the top of this article. The reason this seal serves as the best introduction to both articles is because, beyond clearly showing John Henry’s ownership and control of MMC, as Holcombe states, it was part of every label of Atwood’s Bitters that MMC (as well as its successor, the Wyeth Chemical Co., as AHP’s manufacturing unit) ever produced.

MMC’S ATWOOD’S BITTERS

In actuality, Henry had to buy MMC’s interest in Atwood’s Bitters from a great many different people (although Littlefield was not among them), and his quest to own Atwood’s Bitters began earlier than 1877. The only clear way to explain Henry and MMC’s involvement with Atwood’s Bitters is to examine all the complex and convoluted litigation that surrounded its ownership. Although MMC’s lawsuit raged for eight years and culminated in a decision by the highest court in the land, the United States Supreme Court, it began in 1875 with a complaint (as all lawsuits do). MMC’s complaint, a thirteen page document, alleged that the firm of Nathan Wood & Son of Portland, ME was engaging in unfair competition because: a) Wood was illegally manufacturing and selling an inferior and unauthorized formulation of Atwood’s Bitters in the same distinctive 12-sided bottles with the same wording molded into the glass bottles and with virtually the same label as MMC was using; b) was doing so with the intent both to defraud the public and to steal business from MMC and; c) by doing so, was benefitting illegally from the vast sums of money that MMC was expending to advertise the Bitters. The lawsuit sought immediate relief in the form of an injunction, pendente lite (during the pendency of the litigation), as well as permanently barring Wood from using the name Atwood’s Bitters or any of the elements of its presentation, such as the formula, the bottle and the label, all of which MMC claimed it owned exclusively, as well as damages in the form of payment by means of an accounting for all of the sales Wood had illegally stolen from MMC by selling its phony Atwood’s Bitters.

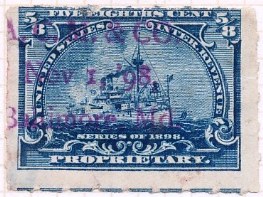

NATHAN WOOD & SON CANCEL ON BATTLESHP REVENUE STAMP

NATHAN WOOD & SON ATWOOD BITTERS

BOTTOM OF BOTTLE SHOWS MANUFACTURED FOR NATHAN WOOD & SON

Such complaints as MMC filed were fairly common and standard at the time because the legal field of unfair competition was still in its infancy in the United States. Among patent medicines, when one became popular, it was often shamelessly exploited by all manner of copiers hoping to cash in on the profits while the craze for that particular medicine lasted. U.S. law had to grow to define which ideas and designs were entitle to legal protection against copying and the circumstances under which such protection applied. What spurred the Atwood’s Bitters litigation, however, was a slightly different problem that stemmed from economics rather than simple unfair copying.

MOSES ATWOOD INVOICES

In 1840, a product, like Atwood’s Bitters, began as a local phenomenon in one place, like northeastern Massachusetts, and then spread throughout a region, like New England. The means of transportation before the Civil War just did not provide the means to make the market bigger, unless one was a singular genius like Demas Barnes, who allied himself with a number of different regional pharmacy networks and mediated among them. When Moses Atwood dispensed rights to make and sell his Bitters, he did it by location or customer route. However, by 1875, the nation’s railroads had expanded enough to make the market national and shipping was mechanized enough to offer the prospects of international markets. As John F. Henry struggled to control manufacture of the Bitters, he encountered a list of owners of the Bitters that rivals a list of biblical “begats.” The real problem in his lawsuit became not that people he was suing had illegally copied the Atwood’s Bitters, but rather the issue of whether they owned as much legal rights to manufacture it as he did. The question ultimately boiled down to whether Henry had sufficiently stuffed ownership rights to the Bitters back into the shattered genie’s bottle that Moses Atwood had broken and he was trying to reassemble.

MOSES ATWOOD

While the Bitters did begin with one Moses D. Atwood (1810-1892)³ in 1840, Atwood soon brought his father Levi, his brother, Levi F., and son, Moses F., into the business. By 1842, he had also entered into a partnership agreement with a local druggist, Lewis H. Bateman, as well as another individual, George Bingham, a botanist from Atwood’s home state of New Hampshire. Sometime in the 1840s, he also granted his brother and his father the right to manufacture and sell the Bitters in certain areas of Maine. In 1848, he sold to Moses Carter of Georgetown, MA distribution rights to various places in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York, provided he supplied the formula Carter sold. In 1852, he and Bingham sold a further interest in the Bitters to Carter and his Carter’s now partner Benjamin S. Dodge, a self-described “farmer” who lived in nearby Rowley MA, three miles away from Georgetown. Carter & Dodge later took in Carter’s son Charles L. Carter as a third partner. Finally, in 1855, Atwood moved West to Iowa after he and Bingham signed a contract conveying all the remainder of their interest to Carter & Dodge, seemingly reserving to Atwood only the right to sell the Bitters west of Illinois, which Atwood apparently never attempted.

M. CARTER & CO. CANCELS ON CIVIL WAR REVENUES

So in 1855, after Atwood sold out, did Carter & Dodge own the Bitters outright? In a word, no. When Carter & Dodge sued Bateman in Massachusetts State Court, in a suit that lasted from 1857 to 1860, to stop him from selling his own Atwood’s Bitters, that Court found that none of the earlier transactions between Atwood, Bingham, Carter and Dodge properly accounted for Bateman’s interest in the Bitters and refused to enjoin Bateman from making and marketing his own Bitters. Yet Carter & Dodge marketed their Bitters for several years, while Batemen, whom the Massachusetts Court found had actually received the recipe for the Bitters from Atwood, made little attempt to exploit it, particularly while Carter & Dodge were suing him.

1869 M CARTER & SON INVOICE

M. CARTER & SON ATWOOD’S BITTERS

When Dodge dropped out of Carter & Dodge in 1858, the business continued as M. Carter & Son, with Moses Carter and Charles L. Carter as the principals. Later another son, Luther F. Carter, joined his father and brother. Then the business name became M. Carter & Sons, when Charles L. Carter left the business and his brother, M. Frank Carter, joined it. The business returned to the name M. Carter & Son after Moses Carter, the father, died in 1870, and a year later, Luther F. Carter bought out his brother M. Frank. Apparently many of the bottle variations of Atwood’s Bitters arise from the changing nature of the Carter’s ownership of the Bitters. While the testimony and circumstances are murky, the Carters, and those who claimed their interest in the Bitters through the Carters, also seem to have been responsible for there existing two different strength Bitters, one of which wholesaled for about $15 to $16 per gross of bottles (144) and the other of which retailed for $27 per gross.

1870 M. CARTER & SONS AD

In the meantime, after Dodge left Carter & Dodge, he manufactured his own Atwood’s Bitters in Rowley MA using Atwood labels for about five years, while also, in 1867, selling the right to manufacture the Bitters for five years to William B. Dorman another drug store owner in Georgetown MA. Before that term ended, Dodge sold a further right to manufacture the Bitters to Noyes & Manning, a pharmacy located in Mystic CT.

1875 BATEMAN AD

Along with all these manufacturers, in the late 1850s, Moses F. Atwood, the son of Moses D. Atwood, returned from the West to Massachusetts and began making the Bitters again, this time with Bateman, who issued a circular asserting his right of ownership to the Bitters. Bateman continued to market these Bitters as Atwood’s Bitters until his death in 1871 and his son, also Lewis H. Bateman, continued to do so after his death. The only distinguishing mark between the various Carter permutations of Atwood’s Bitters and Bateman’s Atwood’s Bitters was that Bateman printed his own facsimile signature instead of Moses Atwood’s across the label to verify the medicine. However, in 1861, Moses F. Atwood sold his interest in the Bitters to Nathan Wood, who became the defendant in MMC’s 1875 lawsuit. Atwood then went off to fight in the Civil War, where he created a distinguished record. While he and his father had careers in the West that stretched on for several decades, the Atwoods drop out of the Bitters ownership record after 1861. Although one witness in the MMC litigation went so far as to claim that there were six different Atwood’s Bitters being sold at the same time, the record demonstrated there were at least three varieties of the Moses Atwood’s Bitters known and recognized in the trade: Carter’s, Bateman’s and Noyes & Manning’s (which were known as Mystic Atwood’s Bitters after Noyes & Manning’s location).

1879 MMC AD WHILE LITIGATION PENDING

Now John F. Henry was no fool and MMC did not commence its lawsuit against Wood lightly. Knowing that the ownership of Atwood’s Bitters had been splintered over the years, MMC had assembled its interest in the Bitters quite carefully. In its lawsuit, it presented to the court contracts of sale showing that it had purchased individually the manufacturing rights to the Bitters from no less than a dozen separate people; 1) the four heirs of Lewis H. Bateman Sr. whose rights the Massachusetts Court had earlier found Carter & Dodge had never controlled; 2) Moses Carter’s former partner, Benjamin S. Dodge and his assignee William B. Dorman; 3) Dodge’s other assignee Noyes & Manning, as well as Noyes and Manning individually; 4) Moses Carter’s successor in business, Luther F. Carter and his sometime business partner, his brother, M. Frank Carter; and 5) separately, the other potential Carter successors, Charles L. Carter and the two other children who were the remaining heirs of Moses Carter.

M. CARTER & SON ATWOOD’S BITTERS

Since MMC had bought up the all the rights that Carter and his family had held, plus the rights that Dodge had held and transmitted to others as well as the Bateman rights that Carter & Dodge had never held, MMC’s felt it owned all the legitimate interests that Moses Atwood had transmitted. Henry could show his ownership of Carter’s, Bateman’s and the Mystic Bitters. He had put the ownership genie back into his own bottle. To further bolster his claim, he even obtained all the way from Iowa the affidavit of Moses D. Atwood himself swearing that Bateman’s circular claiming ownership to the formula was a fraud and further affirming that he had conveyed the Bitters formula to Carter & Dodge in 1852 and the rest of his territorial rights to them in 1855. MMC’s contention in the litigation was that Nathan Wood had purchased his rights to the Bitters from the one person who never had held an ownership interest to sell, Moses F. Atwood, Moses D.’s son. Certainly, it conceded Moses F. had been employed both by his father and by Bateman at different times, but that mere employment conveyed upon him no ownership status in the Bitters themselves. Having purchased the rights to manufacture the Bitters from all these disparate parties, surely, MMC had gathered to itself sufficient ownership rights to claim that Wood was an interloper who had purchased from the one party not authorized to sell to him.

LEVI ATWOOD’S BITTERS

The federal District Court in Maine gave careful consideration to all of the ownership interests, but weighed them quite differently than MMC. Pointing to the glaring fact that Moses D. Atwood had chipped off a piece of the ownership of the Bitters way back at the beginning for his father Levi and his brother, Levi F. Atwood in the 1840s, the District Court held simply that MMC had never obtained complete ownership of Atwood’s Bitters, and, lacking that complete ownership, found that MMC could not maintain that it had the exclusive control of formula, bottle and label it was claiming Wood’s use had infringed. Oddly, all parties to the litigation, seemingly even MMC, agreed that: 1) Moses Atwood had conveyed to his father and brother ownership interests in the Bitters; 2) Levi F. Atwood had sold his ownership interest to H. H. Hay of Portland, Maine; and 3) Hay was selling another brand of Bitters called L. F. Atwood’s Bitters in Maine all through the period. In fact, while the Court never mentioned it, the testimony of some of the witnesses showed that, prior to commencing the litigation, MMC had tried and failed to buy Hay’s interest even before trying and failing to buy Wood’s interest as well. Apparently after failing at buying these remaining potential interests in the Bitters, when it commenced its litigation against Woods, MMC argued that it simply did not regard Hay’s L. F. Atwood’s Bitters as unfairly or illegally competing with the Moses Atwood’s Bitters because Hay’s packaging and labeling were, and always had been, distinct from that used by MMC and all its predecessors. Moreover, in their pricing guides for retail druggists, trade journals listed at least these two Bitters as separate and distinct from one another and obtainable respectively from MMC and from H. H. Hay & Co. The Court implicitly found that argument to be nonsensical legal hair splitting, ruling that exclusive control over the formula, bottle and label for Atwood’s Bitters followed only from complete ownership of them.

H. H. HAY & CO. REVENUE STAMPS

CANCELS ON CIVIL WAR GOVERNMENT ISSUE REVENUES

CANCELS ON BATTLESHIP REVENUES

In addition – to add insult to injury – the Court found that since MMC and the other successors to Moses Atwood were not him, that singular right to claim on the bottle, packaging and label that the Bitters were prepared and sold by Moses Atwood of Georgetown MA – which Atwood alone had possessed – had long since dissipated as the manufacturing rights had been handed around among all the subsequent owners. Thus, the Court further ruled that MMC, whose factory was in New York City, simply had no right to even ask the Court to use its power to protect MMC’s bottle, label and packaging that explicitly represented that the Bitters were made by Moses Atwood of Georgetown, MA because that claim constituted a misrepresentation upon the public by MMC that the Court would neither countenance nor perpetuate.

H. H. HAY & CO. L. F. ATWOOD’S BITTERS

The Supreme Court did not even trouble itself to review the whole ownership issue in detail. It found the District Court’s second reason sufficient to uphold the District Court’s ruling. It reasoned the party that stood before the Court asking for its help was MMC. After noting the extraordinary value that all parties placed on the designation of the Bitters as being prepared and sold by Moses Atwood of Georgetown MA, the Supreme Court responded: “It is not honest to state that a medicine is manufactured by Moses Atwood of Georgetown, Massachusetts when it is manufactured by Manhattan Medicine Company in the City of New York.” This curt ruling was followed by pages of quotes and citations of mostly English cases illustrating the wisdom of this ruling, and, although that position undoubtedly represents a correct legal principle about unfair trade practice, it reflects a narrow and pedantic view of the manner in which advertising and commerce were developing in the U.S. after the Civil War. After that ruling all of the interested parties revised their labels and bottles to more correctly reflect the name of the manufacturer and the place of origin of their particular product, but none of the parties discontinued their sales of Atwood’s Bitters. MMC just changed the wording on the bottle to “formerly made by Moses Atwood of Georgetown, MA.”

MMC ATWOOD’S BITTERS BOTTLE AFTER SUPREME COURT DECISION

Even without the help of the courts, MMC still sought to stop Nathan Wood & Son from selling Atwood’s Bitters. It persisted in asserting its exclusive right to advertise that its product was the true Bitters originally prepared by Moses Atwood of Georgetown, MA. In 1889, the National Wholesale Druggists Association (NWDA) adopted an internal dispute resolution mechanism for proprietors of patent medicines who felt their trademarks were being infringed. The NWDA authorized an internal commission to hear and rule upon such claims of improper infringement. While the NWDA recognized that the tribunal had no binding legal power, since the NWDA noted that 90% of all patent medicines sold in the US were purchased by its members, and members agreed not to purchase goods from infringers, the NWDA believed it could exercise its great “moral power” to dispose of such claims without the time and expense of litigation. The 1890 report on the activities of this commission included the following terse statement:

Compared with the energy the proprietors spent fighting over the right to exploit the Bitters, the remainder of the history of the Bitters is almost anti-climatic. MMC retained the right to produce Atwood’s Bitters until its sale to AHP in 1929. Holcombe confirms that the Wyeth Chemical Co. division of AHP was still manufacturing them in 1935.* L. F. Atwood’s Bitters, the Bitters that MMC had treated in its litigation as non-competitive, continued to be manufactured by H. H. Hay & Co. until approximately 1915 and one source claims were still being manufactured and sold by another bitters company, Lash’s Bitters Co., as late as 1925.† Nathan Wood & Son was still in business in 1925 as well, but the products it was then known for were flavoring extracts. Perhaps the ruling by the NWDA commission in 1890 had been more persuasive than the courts in finally stopping its manufacture of Atwood’s Bitters. Yet there seemed to be enough of a market, even after the advent of Prohibition in 1920, to attract AHP to the market for medicinal alcohol in the form of bitters.

SAMPLES OF HALL & RUCKEL CANCELS

The real mystery is what happened to MMC itself after John F. Henry died in 1893. It soon closed its offices in Manhattan, but continued to exist, really without substance, until its sale to AHP in 1929. The best explanation for MMC’s virtual disappearance appears to be as follows: John F. Henry had a younger brother, Frank S. (1846-1914), who had worked with him as his “jobber,” (traveling sales representative), for more than fifteen years after the Civil War, visiting every state in the United States and even journeying as far as the Hawaii, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand on behalf of his brother, before leaving to cut his own figure as a jobber for another old New York City firm, Hall & Ruckel (H & R). that had done business largely in the wholesale drug trade (and which will some day get its own column as well). When John F. Henry died, Frank appears to have arranged for H & R to take control of the marketing and manufacture of all of John F. Henry’s products, including Atwood’s Bitters. Shortly thereafter, in 1895, just after the death of its own founder, William H. Hall, H & R reorganized its operations and became solely a manufacturer and proprietor of patent medicines (of which it had a number of best sellers itself) while selling its wholesale operation to a recently founded company, C. G. Bacon & Co. While Frank Henry chose to move to the Bacon company to continue as a jobber (and later went on the become the founder of yet another patent medicine company in Cleveland that someday will find itself profiled in this column), he seems to have entrusted his brother’s legacy to H & R’s care. Up until 1913, it was listed in a trade journals as the proprietor of Atwood’s Bitters, and during the same period, it was applying in the United States Treasury Department to collect authorized rebates on customs duties charged on imported alcohol used in their manufacture. As will be discussed fully in its own column at some subsequent future time, H & R remained an independent company throughout the first half of the Twentieth Century, but for this article’s purposes, it is enough to say that Atwood’s Bitters did not remain with it.

1922 TRADE AD SHOWING O. H. JADWIN AS AGENT FOR ATWOOD’S BITTERS

Beginning in 1914 (coincidently the same year as the death of John F. Henry’s brother Frank), another company began to make the applications for the alcohol rebates in connection with the manufacture of Atwood’s Bitters. It was none other than O. H. Jadwin & Sons, and, by 1922 (possibly because H & R itself was under second generation leadership), Jadwin had supplanted H & R in the trade journal listings as the agent for Atwood’s Bitters and the other former MMC products. Yet the shares representing MMC’s ownership of Atwood’s Bitters and these other products must have remained in the hands of John F. Henry’s heirs, for AHP purchased, not an operating factory that was producing goods, but rather MMC’s capital stock, and with it the right to produce Atwood’s Bitters. AHP’s founders, particularly Jadwin and the advertising man Murray, must have been very persuasive that they were the best management to keep Atwood’s Bitters and the other MMC products popular because, as with so many other companies examined in prior articles, once MMC’s products were handled by Jadwin, MMC seems to have spiraled inevitably and ultimately toward absorption into AHP. By 1935, as Holcombe reported, Atwood’s Bitters were being produced by AHP’s Wyeth Chemical Co., but still bearing the portrait of John F. Henry.

WYETH CHEMICAL CO. ATWOOD’S BITTERS

x——–x

¹ In his article about MMC, Holcombe describes, but never illustrates, its private die proprietary stamps and admits that the portrait in the center of the stamps is unidentified. Sadly, almost 100 years later, the portrait still is unidentified.

WYETH CHEMICAL CO.’S VERSION OF THE HENRY FACIMILE SEAL

² A non-monetized seal closely resembling the design of Civil War private die proprietary stamps that manufacturers employed after the tax was discontinued because they wished customers to continue to identify such “stamps” with the products since people had come to assume the tax stamp was part of the packaging of the medicines

³ See how one writer sought to identify the proper Moses Atwood in a thoughtful article at Meyer, Ferdinand “Moses Atwood – Atwood’s Jaundice Bitters – Georgetown MA.” Peachtree Glass. 2 Apr 2018. peachtreeglass.com//2018/04/moses-atwood-atwood’s-jaundice-bitters-georgetown-MA

WHITEHALL PHARMACAL CO. ATWOOD’S BITTERS

∗ Other extant bottles confirm that AHP at some later point transferred manufacture of the Bitters to its Whitehall Pharmacal Co. division, and a 1948 trade listing indicates that they are available from that company. They ultimately became known as Atwood’s Jannaice Laxative, “jannaice” being a term registered as a trademark by MMC in 1929 (although appearing on seemingly earlier labels and bottles and presumably used earlier by it, Hall & Ruckel or O. H. Jadwin & Sons, possibly as a more medically innocuous term than “jaundice”). Registration of the jannaice trademark was transferred by MMC to Whitehall Pharmacal Co. in 1949.

† Possibly AHP was finally able to accomplish what John F. Henry was unable to do by either purchase or litigation because among the Atwood’s Bitters bottles there is one whose label reads “L. F. Atwood – none genuine without the signature” followed by “Wyeth Chemical Co, Distributor” listing its New York City office address. That combination would indicate that AHP, without fanfare or even public notice, had brought the L.F. Atwood interest back together with the Moses Atwood interest and finished repairing Moses Atwood’s smashed genie bottle of Bitters ownership.

© Malcolm A. Goldstein 2020

Sterling Products Inc. (VI.1.a) – American Home Products

Sterling Products, Inc., Manufacturer

Chapter 6.1.a: American Home Products

AMERICAN HOME PRODUCTS CORP. SPECIMAN STOCK CERTIFICATE

In 1926, Sterling created yet another subsidiary, this time a holding company, to aid it to swallow and digest more patent medicine, drug and pharmaceutical companies. It was named American Home Products (AHP), and, as its name implied, its reach ultimately extended far beyond the over-the-counter medicine business. With the creation of this division, the pace of acquisition and complexity of the interactions among the various companies appears to have increased exponentially, but the seeds for this amalgamation actually were laid years before. Yet throughout virtually all of its history – essentially until its last ten years of existence – AHP, like Sterling itself, maintained the companies it absorbed largely intact, advertised its constituent brands separately product-by-product and publicized its own name so sparingly that it was referred to in the industry as “Anonymous Home Products.”

POSSIBLE WYETH CHEMICAL CO. BATTLESHIP REVENUE CANCELS

While AHP sprang seemingly full-grown into existence, different accounts of its formation list its constituent parts differently. A 1947 Federal Trade Commission report (discussing potentially monopolistic consolidation occurring within the drug industry and using the credit rating compilation Moody’s Manual of Industrials as it source) showed the initial companies as Wyeth Chemical Co., Petrolagar Laboratories, Edward Wesley & Co. and the Larned Co. A 1949 chemical industry handbook named the initial companies only as Wyeth Chemical Co., Deshell Laboratories, and Edward Wesley & Co. Although these differences are small, subtle and perhaps ultimately insignificant at this late date – and neither is anywhere near close to a complete disclosure of the constituent parts of AHP even at the beginning – they serve to illustrate the difficulty of unearthing and reconstructing the interrelationships that ultimately joined so many family owned or sole-proprietor patent medicine companies into the global conglomerate AHP. A minute and detailed examination of those records which remain readily available to be searched, however, demonstrates that these various companies were already so intricately intertwined even before the formation of AHP that one contemporary drug trade magazine characterized the new grouping by saying: “[t]hese companies … have been owned and managed by Sterling Products interests.”

1912 WYETH CHEMICAL CO. INVOICE

POSSIBLE WYETH CANCEL ON 1919 PROPRIETARY REVENUE

There is no ambiguity about the new corporation that emerged. AHP was incorporated in Delaware on February 4, 1926. The same three Wall Street firms that had financed Household Products, Inc. in 1923 acted as its underwriters and brokers for sale of its shares. The principals of the new company were William E. Weiss, Albert H. Diebold, and Stanley Jadwin, all of whom already sat on Sterling’s board, as well as William Kirn (1871-1942) and Walter D. Rowles (1867-1928), both of whom held significant positions in the Detroit drug wholesale drug firm of Parke, Davis & Co., and John F. Murray (1871-1936), who headed his own advertising agency. According to a booklet published for AHP’s 75th anniversary, the initial AHP management board of six (“the Principals”) was assembled carefully with Weiss and Diebold first teaming with Murray and then bringing Jadwin aboard to provide expertise about the interworkings of the drug trade. Kirn and Rowles were added to make the manufacturing facilities of Parke, Davis available to AHP. This account, while not contradictory, does not jibe entirely with the history of Sterling already unfolded in these columns, because Jadwin was a part of Sterling and the two Parke, Davis members already had strong pre-existing ties with Sterling’s management, since, as chronicled in an earlier article, Parke, Davis was Sterling’s contractor to manufacture Sterling’s Knowlton Danderine. The difference in the storytelling approaches might be a reflection of the circumstance that AHP’s anniversary booklet was written in 2001, decades after Sterling and AHP had separated from one another as business entities, and AHP, at that point attempting to refocus its public image from being Anonymous Home Products to being a progressive, forward-looking pharmaceutical giant, no longer wished to recall that it had begun as a division of Sterling.

WHITEHALL PHARMACAL CO.’S ROWLES RED PEPPER RUB

Each of the Principals had additional tendrils in the drug business that helped to shape AHP as well, and AHP’s history states that when they began to consider launching a consolidated management in the early 1920s, they held interests in sixteen different patent medicine companies. Present records readily available do not allow that claim to be verified, but there is no reason to doubt its accuracy. Among the non-Sterling men, Kirn, as well as being head of Parke, Davis’s Private Formula Department, was also was serving as President of the Larned Co., possibly accounting for the difference between Moody’s explicit listing, and the industry handbook’s omission, of this company in the table of AHP’s constituent corporations. Rowles, while head of the Special Preparations Department at Parke, Davis & Co., apparently already had two remedies bearing the Rowles name marketed through a company called Whitehall Pharmacal Co., another patent medicine company that emerged sometime around 1920 and which AHP immediately recognized as one of its divisions. In the consolidation that followed the establishment of AHP, Rowles’ Red Pepper Rub – a medicine intended for conditions that required the application of heat and to replace old-fashioned plasters – was later manufactured under the Wyeth Chemical Co. name. While Kirn and Rowles – who was based in Parke, Davis’s New York City office and lived in a house in Montclair, NJ that was both elegant and grand enough to be featured in American Homes and Gardens in 1910 – were in the pharmaceutical field, it was Murray – the last of AHP’s founding managers – who not only brought his ad agency into the new firm as its in-house advertising department – a status it held for the entirety of AHP’s nearly eighty year existence -, but was pivotal in bringing many of the smaller patent medicine companies into the conglomerate that AHP became.

1905 & 1920 POSTCARD VIEWS OF WHITEHALL BUILDING

Murray emerges as the wildcard in the organization of AHP. Born in Waterloo, Iowa in 1871, he was one of those Nineteenth century characters who ran away from home to “join the circus.” It is a pity that there appears to be no extant picture of him because the AHP anniversary booklet describes him as follows: “a dandy, an immaculate dresser who ‘always looked the answer to a maiden’s prayer,’ said one colleague.” After working as a traveling show musician and barker, he had settled briefly in Chicago where he was employed by William Wrigley, Jr.¹ to compose jingles for Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit gum and developed an interest in the advertising business. As George Rowell before him had learned, to advertise, one has to have a product to sell, and if one does not have a client to sell for, it behooves the ad man to become the manufacturer. Thus, the behind-the-scenes principal of Whitehall Pharmacal Co. that was marketing Rowles’ Red Pepper Rub turns out to have been none other than John F. Murray, whose ad agency had its offices at 17 Battery Place in lower Manhattan, a building otherwise known as the Whitehall Building. As well as providing the name for Murray’s own patent medicine company, the Whitehall building became the first headquarters of AHP. Not only did Murray participate behind the scenes in the ownership and management of many of these companies, as will become apparent, but, even if there had not been as much interlinked ownership as the record reveals before 1926, the proximity of the ads of many of these constituent smaller patent medicine companies well before their merger into AHP suggests that a single advertising company – Murray’s – was controlling the placement of their ads.

WYETH’S SAGE & SULPHUR COMPOUND

According to AHP’s anniversary booklet, it was Jadwin who suggested to the others that the proper product to build the new entity around would be Wyeth’s Sage and Sulphur Compound which was manufactured by the Wyeth Chemical Co. Originally, it had been touted as a medicine to clean the scalp and promote hair growth, but was later advertised as an elegant hair dye. However, this version of the story puts the cart before the horse by suggesting that Jadwin sought the product out especially for AHP. A more detailed look at the circumstances surrounding the acquisition of the Wyeth Chemical Co. shows that the product arrived well before the notion of AHP existed, for the owners of Wyeth Chemical Co. were the very same men who became the principals of AHP. When the product name was trademarked in 1909, the name was said to have been in use since 1888, although it apparently had appeared as early as 1885 in the catalogue of the pharmaceutical company McKesson-Robbins (yet another company to be profiled anon in this column). The original proprietor of the Compound was a man named John L. Wyeth, a chemist from Rochester, N.Y. Its origins are shrouded in mystery at this time, but when Wyeth was forced to file for bankruptcy in Rochester in 1905, a dispute arose as to whether he, or his mother, who claimed that his father had developed the formula, actually owned the product. Ultimately, he must have prevailed, because he earned his discharge from bankruptcy in 1906, and by 1909 had sold the product to none other than the very same group of individuals who changed chairs in 1926 to become the governing board of AHP!

WYETH CHEMICAL CO.’S ROWLES RED PEPPER RUB

Thus, what is most striking about the 1909 ownership change of Wyeth Chemical Co. is that at the very moment when Sterling’s antecedents were coalescing in the form of its predecessor, the Neuralgyline Co., Weiss, Diebold and Jadwin had also begun operating the Wyeth company as well, completely separate and independent from their Sterling project, thus foreshadowing the formation of AHP by seventeen years. In fact, from 1909 on, Stanley Jadwin (1877-1936), was president of Wyeth Chemical Co. and, by 1919, the ad man John F. Murray was its other officer and director. Exactly why Sterling kept the other group of companies which became AHP publically separate for so long is difficult to gauge at this remote time. Certainly, fear of being labeled a monopoly never seems to have been a serious concern of the pharmaceutical industry. As will be shown in subsequent articles, when AHP was announced, Sterling was at the beginning of its most ascendant monopolistic phase, and only the economics of the Depression seems to have thwarted its plans to dominate the “household products” industry. Certainly periodic Congressional investigations have never cowed any pharmaceutical company from expanding and the prices which “big pharma” charges for drugs remains a current and on-going topic of public discussion. Viewing the situation from a distance of approximately one hundred year, the most striking element of difference between Sterling and AHP was the involvement of Murray in AHP. Possibly the two entities were kept separate because Sterling’s ad campaigns were being run by the Thompson-Koch ad agency which it had purchased as part of its deal with Pape, Thompson & Pape. As will be shown below, even that hypothesis is purely speculative because other Pape holdings which became part of AHP wound up being represented by Murray’s ad agency.

1917 O. H. JADWIN SONS’, INC. COVER

When AHP was formed, Sterling’s principals were at the top of their game, and, because of their purchase of Bayer’s American properties, were considered among the sharpest and most well-financed in the business. Because Weiss and Diebold were the foremost managers of Sterling’s affairs, the salient events of the lives have been outlined already in earlier chapters of this series of articles, but Stanley Jadwin’s background and family require a moment’s attention as well. He came from a family not only steeped in the pharmaceutical business, but one that had also attracted grisly, momentary national infamy in 1913. Since 1683, four generations of Jadwins had been Virginia planters before his grandfather moved to northeastern Pennsylvania in the 1830s to be a shoemaker and to raise his family of eight children. His father, Orlando (1833-1911), the oldest child, began a pharmacy and wholesale drug business with some of his younger brothers in Carbondale, PA, near Scranton, in 1856 and later moved to New York City in 1866 to found his own immensely successful wholesaler drug business, O. H. Jadwin & Sons.² Orlando continued his father’s tradition of having a large family by fathering at least nine children of his own, among them four sons. His boys became the “sons” part of the burgeoning and prospering family business, and, in due course, the two oldest, Palmer (1868-1922) and Paul (1874-1942), took over its management upon his death, while Stanley, the third, as well as being the third officer of O. H. Jadwin & Sons, had already branched out into his own larger pharmaceutical ventures.³ As noted in connection with the formation of Neuralgyline Co. earlier, Stanley Jadwin’s connection to the Jadwin firm had given the fledgling Sterling group entry into a national distribution network, and that advantage was also now available to AHP. He had been deeply involved in Sterling’s acquisition of Bayer, and, by 1920, had expanded his business universe beyond the pharmaceutical industry and was also a director of two New York City banks and a New York City street railway company.

JAD SALTS, AS LATER MARKETED BY WHITEHALL PHARMACAL CO.

LIMESTONE PHOSPHATE COMPOUND, AS LATER MARKETED BY WYETH CHEMICAL CO.

Jadwin and Murray, were also the officers and directors of the Jadwin Co.’s subsidiary, the Jad Salts Co., manufacturer of Jad Salts, the major proprietary medicine O. H. Jadwin & Sons had itself developed and promoted, which now also was folded into AHP, as well as another minor subsidiary company, the Limestone Phosphate Co, which brought its compound for stomach settling and acid neutralizing into AHP. Already in 1916, however, the state of Connecticut testing laboratory that evaluated quack products warned about Limestone Phosphate: “The use of the word ‘Limestone’ in connection with this product is totally unwarranted, and is most misleading in spite of the word ‘brand’ which appears on the package in small letters.” Essentially, the laboratory found it to contain no lime at all and characterized the product as equivalent to bicarbonate of soda, otherwise known as baking powder. The report indicated that the product might have a slightly purgative effect, in other words, yet another laxative.

1885c ELY BROS COVER FROM OWEGO, NY

1885 AD FROM OWEGO NY & 1891 AD FROM NEW YORK CITY

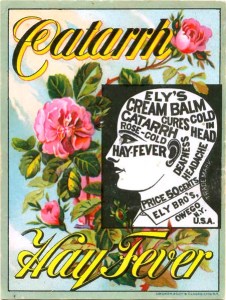

COLORFUL ADVERTISING FOR ELY’S CREAM BALM

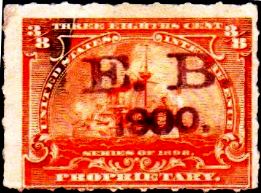

1898c ELY BROS. BATTLESHIP REVENUE CANCELS

PACKAGE SEAL USED BY ELY BROS.

ELY’S CREAM BALM, AS LATER MARKETED BY WYETH CHEMICAL CO.

The Wyeth Chemical Co. also had a subsidiary. It brought with it to AHP an older proprietary medicine, Ely’s Cream Balm, used for treating “catarrh,” a Nineteenth Century term for any kind of vague general disability or inflammation, particularly those involving excessive mucus discharge, much like the modern usage of the terms “cold” or “flu.” The Balm had previously been manufactured by the Ely brothers, Alfred (1844-1917), Charles (1846-1927) and Frederick (1853-1914c), of Owego, NY, in the Southern Tier of Western New York State along the Susquehanna River. The brothers opened a retail drug store in Owego in 1868, but later, around 1885, also created a Manhattan office. Eventually they all decamped to New York City and ran their entire operation from their New York office. As with virtually all Nineteenth Century entrepreneurs, the Ely brothers invested in other ventures beyond manufacturing a patent medicine. Their older brother, Edward, became involved in a tool making business called the Trimont Manufacturing Co. located in Roxbury, MA, and, in 1889, Alfred, Charles and Frederick were all named as assignees of a patent on the design of a mowing machine used to harvest grain fields, possibly for manufacture by Trimont. Charles seems to have left the patent medicine business in the 1890s, and in 1902 became president of Trimont after Edward’s death. A sometime poet, Charles was prominent enough to earn a profile in the 1925 Supplement to the Cyclopedia of American Biography. While he continued to make large and generous donations to the library he left behind in Owego, he never moved back to his home town and died in Boston at age 81 in 1927. Ely’s Cream Balm continued to sell, and Alfred and Frederick were still both named in the New York City business directory in 1910. By 1915, Alfred alone appeared in the directory, and by 1918 even he had disappeared and Stanley Jadwin was listed as president of Ely’s Cream Balm Co.

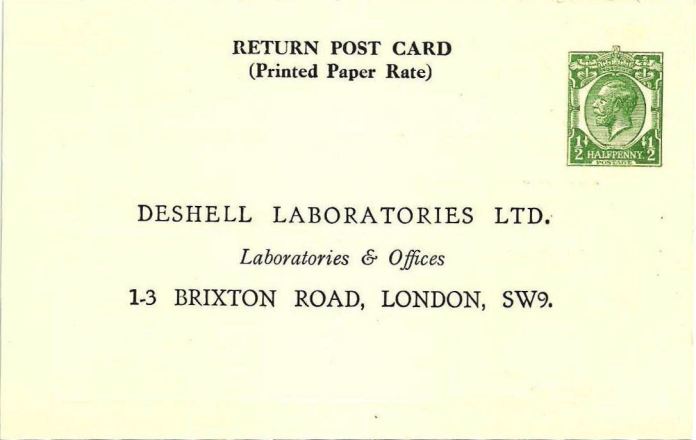

1920c DESHELL LABS (ENGLISH OFFICE) RETURN POSTCARD

1937 PETROLAGER LABS INVITATION TO A DOCTOR

PETROLAGER

Deshell Laboratories, the second of the named AHP-melded companies, and Sterling’s only outside acquisition, was located in Los Angeles, CA. AHP’s anniversary booklet suggests that Sterling sought out the company precisely because it was different from all of the other companies that the Principals already had interests in. Its product was a laxative named Petrolagar, and the Deshell name soon was replaced by Petrolagar Laboratories, again perhaps accounting for the confusion as to which company was part of the initial consolidation of AHP. Unlike any of the other medicines that the Principals held shares of, Deshell advertised the compound as an ethical preparation (that is, strictly to doctors). While it seems a bit hard to imagine now because of the impact of Sterling’s acquisition of Bayer’s interests and the advertising juggernaut AHP later became, the AHP anniversary booklet states that when the Principals sought financial backing for AHP, the Wall Street firms initially were unwilling to back the venture because of concerns that as growing scientific inquiry exposed the typical exaggerated claims of their over-the-counter-type medicines as outright quackery and potentially dangerous to the public, the public would eschew them. The bankers felt that Sterling and AHP ought to have available a laxative that doctors could actually prescribe, beyond relying upon time-tested folk brands like Phillips Milk of Magnesia and Fletcher’s Castoria. The AHP history also states that the Principals liked DeShell as an acquisition because it had already established overseas offices which they could capitalize on. In light of Sterling’s prior history, including its purchase of Bayer’s assets, this view only serves to demonstrate that by the time the history was written in 2001, Sterling and AHP had been operating as separate companies long enough for AHP to have forgotten that it began as a division of Sterling.

PETROLAGER ADS WITH WALL PRINTS FOR DOCTOR’S OFFICE

Nevertheless, according to the AHP history, Petrolager was the perfect product to suit the Principals’ needs. Because he felt the world was ready for a palatable laxative, ex-President Theodore Roosevelt’s own physician had commissioned its development from a Russian immigrant pharmacist named Channon A. Deshell (1875-1947) who had settled in New York City. DeShell came up with a formula of mineral oil, agar and extract of maraschino cherries. Roosevelt himself took the first dose prescribed and pronounced it to look and taste like ice cream, and, with TR’s endorsement, Petrolager was off and running. Agar is a jelly-like substance derived from algae. Because it is composed principally of polysaccharides, it is still commonly used as culture medium for microbiological work, and in the kitchen as a thickening agent for various foods. Petrolager itself came in five varieties, depending on the severity of the constipation and the accompanying symptoms. When Sterling’s managers met DeShell, he had moved to Los Angeles where he had tried to own and operate a drug store before deciding to concentrate on his own research and manufacturing. He was content to sell the company to the Principals and continue to work there researching and patenting agar compounds for the rest of his life.

1919 EDWARD WESLEY CO. TRADE ADS

WESLEY CO.’S FREEZONE

The men behind Edward Wesley Co. (sometimes called Edward Wesley & Co.), the third named AHP constituent company, were familiar to the Principals. They were William Weiss, another member of the Diebold family, Arthur H. Diebold, and the Pape Brothers, Edward H. (1877-1926) and Harry W. (1876-1928), Cincinnati patent medicine manufacturers whose company, Pape Thompson & Pape, had already sold itself and its product line, including Pape’s Dia-pape-sin, to Sterling in 1909, together with its ad agency, Thompson-Koch. The Papes had been involved in a number of different patent medicine ventures in and around Cincinnati in the early 1900s until they found their niche with Pape, Thompson & Pape. After the sale, they stayed with the company and kept looking for other promising patent medicines. They organized the Wesley company in 1915 in Cincinnati, OH, and garnered success advertising a number of products, most notably Freezone, a corn removing compound, and Fluff, a beauty shampoo.

1883c W. H. HILL & CO. COVER FROM FAIRPORT, NY

1887 W. H. HILL & CO. POSTCARD FROM DETROIT MI

1898c W. H. HILL & CO. BATTLESHIP REVENUE CANCELS

1902 & 1904 W. H. HILL CO. CALENDARS

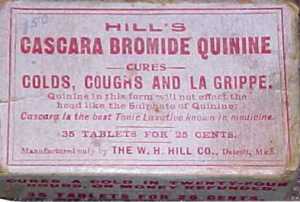

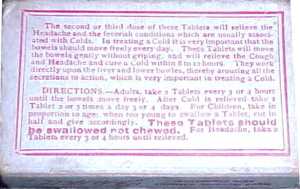

HILL’S CASCARA BROMIDE QUININE BOX SHOWING TORN REVENUE STAMP

The last named piece of AHP was Larned Co. (named apparently for the street in Detroit on which it was located). It was a corporation formed in 1924 to purchase, at a cost of over a million dollars, Hill’s Cascara Bromide Quinine, previously manufactured by W. H. Hill Co., a Detroit patent medicine manufacturer. Hill was another of the Nineteenth Century’s class of self-made millionaires. Born in 1852 in Cohocton, a small town in the Finger Lakes Region of Western New York, he moved to Michigan with his family in 1870 and became its main breadwinner after his father, a successful doctor, died in 1872. In the late 1870s, he became a clerk and traveling salesman for a Pittsburgh drug wholesaler. By 1880, he had learned the drug trade well enough to open his own proprietary medicine factory in Fairport, a town just outside Rochester, NY. After his factory burned down in 1885, he relocated to Detroit MI, where he manufactured an entire range of goods such as Peerless Cough Syrup, Peerless Worm Specific and Kidney Kascara Tablets. From 1880 to 1892, he traveled extensively around the country to establish his product line, and by the time tax stamps were required during the Spanish-American War, his business was big enough to warrant his devising his own distinctive cancel, some of which are shown above. His signature product, Hill’s Cascara Bromide Quinine, was advertised as curing “coughs, colds and la grippe” as well as, again, being a most effective laxative.

1906 & 1924 W. H. HILL CO. COVERS

As a successful businessman, Hill enjoyed all the perks that went with the income. As well as running the W. H. Hill Co., he took on the presidencies of the Ideal Register and Metallic Furniture Co. of Detroit and the Detroit Silk Glove Co. He proudly identified as a Congregationalist and a Republican, and served on the boards of directors of several prominent social clubs in Detroit. He was a golfer and an early automobile enthusiast, with club memberships in the appropriate sporting groups. He also owned the yacht “Titania” and was a member of the Detroit Power Boat Club.

One anecdote, however, might serve best to illuminate the fundamental toughness of Hill’s character. Several years after Hill sold his company to the Larned Co., he was sued by a former minority shareholder in the original W. H. Hill Co., who claimed that he had been short-changed of his share of the spoils that Hill had amassed from the sale. In the laissez-faire age before the Depression, the trial court dismissed the case following the then-current norms of business law which held that corporate directors, like Hill, owed no fiduciary duty to their shareholders, like plaintiff, to disclose their knowledge of corporate affairs, even of events such as the impending sale of the company.

HILL’S TABLETS, AS MARKETED BY WHITEHALL PHARMACAL CO.

On appeal, the reviewing court reached the opposite conclusion. It recounted that the plaintiff in the case was a Detroit attorney who had been given stock at the time of the original incorporation of the Hill Co. in 1907 in return for his having represented Hill in earlier litigation against his competitors. Thereafter, this attorney had served on the Hill Co. board of directors until he grew so self-conscious about his growing deafness that he requested his removal from the board. In 1923, he read that the federal government had brought a Pure Food and Drug lawsuit against the Hill Co. and decided to protect his own reputation by selling his Hill Co. stock. While plaintiff attempted to conduct the sale in secrecy, the Court found that Hill soon became aware that plaintiff was trying to sell his stock, both from a broker ostensibly acting on plaintiff’s behalf who in direct violation of plaintiff’s instructions contacted Hill, and also, oddly enough, from one of Hill’s own rivals, a man named Grove (another fellow who will get his own article some day) who tipped Hill off that he, Grove, had been solicited by plaintiff’s representatives to make an offer to purchase plaintiff’s stock. The reviewing court found that Hill not only had blocked plaintiff’s representatives from getting a true picture of the company’s finances and directed that they instead be shown financial statements from a prior year reflecting losses, but also that Hill had contacted plaintiff’s broker offering him a standard commission and a bonus if the broker could conclude the deal at Hill’s price. The court even found that Hill had conspired to prepare a misleading stock valuation sheet for that broker to show to plaintiff. Since Hill had succeeded in purchasing plaintiff’s stock at the lower price he was offering plaintiff, the Court found that Hill’s interference with plaintiff’s sale went so far beyond the conduct of ordinary corporate business as to constitute fraud. It directed the trial court to conduct a proper accounting as plaintiff had requested, but, by the time it issued this order in 1932, Hill was dead. He had died in 1931.

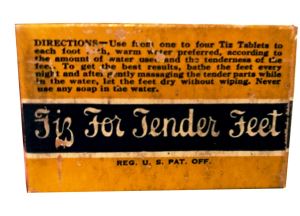

WALTER LUTHER DODGE HOUSE, LOS ANGELES CA

Aside from the big three (or four) companies formally melded into AHP upon its incorporation, it also very rapidly assumed possession of a clutch of other patent medicine companies. Among them was the Walter Luther Dodge Co., which manufactured Tiz, a bath salt, for “tender feet.” Dodge was born in Chicago in 1867 and apparently became a millionaire businessman in that city. However, today he is remembered only in passing as being rich enough to have afforded to relocate his family to West Hollywood, CA and build his family home there between 1914 and 1916. Ranked by the American Architectural Institute as one of the fifteen most significant houses ever built in America and considered universally to be a gem of the Early Modern architectural style, the Walter L. Dodge House was designed by architect Irving Gill (1870-1936), who worked principally on the West Coast. It was constructed of eight inch thick reinforced concrete. Although its innovative marvels included a garbage disposal in the kitchen and an automatic car wash in the garage, its radical departure was its stark reinterpretation of the traditional Spanish Mission style as a sleekly simple geometric form. After Dodge’s death in 1931, the House passed through eminent domain into the hands of the City of Los Angeles whose original intent was to build a school on the site. Although that plan was set aside, the Board of Education operated the grounds for number of years as classrooms for a junior-college-level trade school until 1963 when it deemed the property surplus and available for sale to a private contractor. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors then proceeded to re-zone the entire area as suitable for apartment construction. In a tale of modern urban neglect, the contractor who purchased the Dodge House property from the City suddenly demolished it in 1970, over the anguished outcries of many notable architects, replacing it with a nondescript apartment building.

TIZ FOR TENDER FEET, AS MARKETED BY THE LARNED CORP.

1907 & 1909 HILO GUM CO. ADS – THE POSSIBLE “MISSING LINK”

Although there are easily over thirty websites mourning and paying tribute to the lost beauty of the Walter L. Dodge House, there is no biography of Walter L. Dodge himself exploring the actions and mind of the man who commissioned this masterpiece from Gill, just the dutiful notation in each article that he derived his fortune from Tiz. Only an inconspicuous listing in a stray volume of a weekly magazine named – in self-explanatory fashion – the National Corporation Reporter suggests a possible key to his involvement in the organization of AHP. A 1905 listing for the newly incorporated Hilo Gum Co. demonstrates that he and John L. Murray, mentioned above as one of the Principals, were two of its organizers. Its major product was actually not gum, but rather vending machines for gum and peanuts, and, while it may not have survived to become part of AHP, its existence serves to explain how Walter Dodge drifted into the AHP orbit. Another possible point of contact between Dodge and AHP might have come through Harry W. Pape, who in 1902 had also invented and patented a ribbon system of delivering goods suitable for cigar and gum vending machines, which were then becoming fashionable, and might have been investigated by the Hilo Gum Co.

1913 TIZ TRADE ADS

According to the one extant article devoted to Tiz, written in 1912 and trumpeting Dodge’s latest marketing tactic of advertising it on outdoor billboards to distinguish it from the vast number of imitators nipping at its heels, Dodge had developed the product over “several years of hard labor” and pushed it to prominence with an expenditure of “over a million” dollars in advertising. He recounted that he had experimented over a substantial period of time to develop a suitable balm for foot pain, but the greatest difficulty he faced was deriving a distinctive name for his new invention. He initially considering using the first two letters of his name, until he asked himself what the product was for, and replied to himself: “why, tis for tender feet.” In that moment of singular brilliance, he was struck with both the name of the product: “Tiz,”spelled with a “z” to make it a distinct word suitable for trademarking, and its catch-phrase: “for tender feet.”

1913 TRADE & 1914 PUBLIC TIZ ADS

At first Dodge ran his business strictly by mail order, engendering enough sales from a single one inch ad in a mail order publication to warrant further investment in the product. Gradually increasing mail order sales, in turn, attracted a few voluntary orders from wholesalers who wanted to be able to offer Tiz to their retail drug store customers. This development prompted Dodge to conduct a trial to see whether it was popular enough to market nationally through the regular and customary distribution chain running from manufacturer to wholesaler to retailer. Tiz was test-marketed in Indianapolis, IN accompanied by a flurry of newspaper advertising to attract attention. Sales were so great that the experiment was soon expanded to encompass Columbus, OH, then Cincinnati, OH and finally Pittsburgh, PA. Dodge was convinced that national distribution of Tiz would work, and continuous advertising “in every good daily and weekly newspaper in the United States” over the next two years secured his fortune. By 1919, Dodge’s ads bore Murray’s ad agency address as its office address.

1922 TRADE AD COORDINATED AMONG COMPANIES WHICH WOULD BECOME AHP (ALL AT MURRAY’S ADDRESS)

* * * * *

ST JACOBS OIL CO.

1880c AUGUST VOGELER & CO. CIVIL WAR PERIOD PRIVATE DIE PROPRIETARY REVENUE STAMPS ON SILK & UNWATERMARKED PAPERS

SEALS USED TO REPLACE REVENUE STAMPS AFTER CIVIL WAR TAX REPEALED

1880c A. VOGELER & CO. COVER

PORTRAIT OF CHARLES A. VOGELER

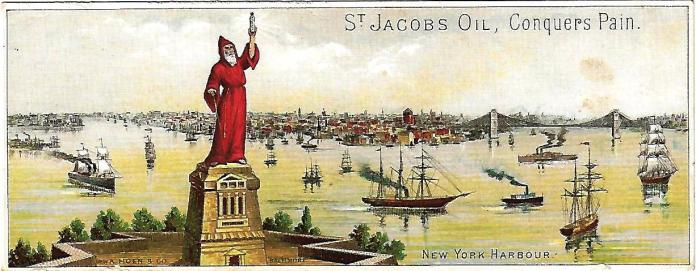

1885c ST. JAMES OIL TRADE CARDS

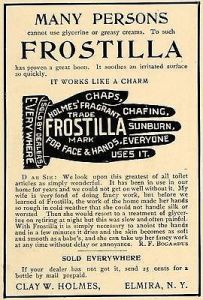

Dodge, as well as Jadwin and Murray, also became involved with another old-time remedy, St. Jacobs Oil, advertised over the years as a pain killer particularly against rheumatism, which also immediately became part of AHP in 1926. The remedy itself had an intriguing history. Its formula was created by Wilmer L. Keller (1846-1906) a Baltimore druggist sometime during the 1870s. He marketed it as Keller’s Roman Liniment, with a picture of Julius Caesar on the label, and achieved little success. However, he did manage to catch the attention of August Vogeler (1819-1908), a solid, reputable and conservative Baltimore druggist in business since 1845, whose son Charles A. Vogeler (1851-1882) was a short-lived, but meteoric marketing dynamo. By the end of the 1870s, the younger Vogeler had purchased Keller’s formula, added some red dye to the mixture and re-christened it as a old German remedy, St. Jacobs Oil. Like virtually all of the nostrums of the time, at first it was touted to be equally good for what ailed men or beasts. Vogeler’s advertising pictured a bearded, red-cloaked monk who vaguely resembled a thin and serious version of our current image of Santa Claus. It was an instant success and immediately became a national best seller.

TRADECARDS AND COVER SHOWING OTHER VOGELER PRODUCTS

The Vogelers conducted a much larger operation than Keller had, and it ultimately featured several different lines of patent medicines at various times, including such concoctions as Dr. August Koenig’s Hamburg Breast Tea, Dr. Bull’s Baby Syrup, Diamond Vera-Cura and Red Star Cough Cure. They were savvy enough to recognize the advertising advantage of availing themselves of the federal government’s offer to allow patent medicine proprietors to negotiate their own printing contracts for revenue stamps during the Civil War tax period, which lasted from 1862 to 1883, since the federal government was using the same private contractors to print both its postage and revenue stamps. When, in the 1930s, Holcombe wrote his articles on United States private die proprietary medicine stamps, the heirs of August Vogeler were still running a remnant of the original company. He consulted them and, as a result, his article on the various stamps and labels they ordered for different splinterings and transformations of the company, including August’s many partnerships with his son Charles and with his son’s friend, Adolph C. Meyer (1852-1914) after Charles’s sudden and very early death, is one of his most thorough and comprehensive, but, sadly, is by no means exhaustive. Nor does it properly reflect the history of St. Jacobs Oil.

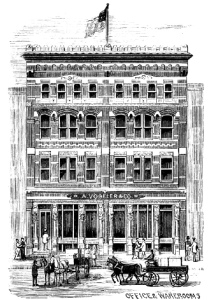

1881 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MAGAZINE SAMPLE ILLUSTRATIONS

An admiring reporter for Scientific American magazine toured the Vogeler plant in 1881 – at the height of the St. Jacobs Oil craze – and wrote about it that: “[w]hile the production of that class of articles known as proprietary specialties may involve no machinery or process not in common use by all manufacturers of drugs, chemicals and the like, the business of advertising and selling them in a large and successful way does involve industrial operations of such magnitude and completeness of organization as to bring the business fairly within the scope of great industries.” The reporter went on to describe the two “business block” sized buildings rising four stories, and the departments that made up the Vogeler operation. On the first floor were the executive offices, the “literary” department, which functioned like that of a “publishing house” in filtering and channeling correspondence received, the “mailing supply” department, which kept all the retailers supplied with advertising to promote the goods, and the shipping department, which dispatched the patent medicines to retailers. The laboratory was located on the fourth floor of the main building and was designed “with ample facilities for the swift and easy handling of crude products and completed preparations, particularly the St. Jacobs Oil, which is the chief specialty” of the company. However, the “distinguishing feature of the house” was its giant advertising department occupying the entire second floor of the building, together with a large plate-glass windowed open area containing receptacles with over ten thousand pigeon holes, one labeled to receive a every newspaper in the nation which published Vogeler’s ads. Copies of each ad run in any such newspaper or periodical were “examined, marked, entered and filed.” The reporter noted with admiration Vogeler’s method of paying for all this advertising: “The unvarying courtesy exhibited toward publishers and the exceptional method of paying advertising bills without waiting for the rendering of statements have established the most cordial relations between the press and the house.” All of this advanced payment was made possible by the book-keeping department’s records that filled 22 ledgers, comprising 12,000 discrete accounts, that were stored in a special safe. The bottling department, which also covered the corking and labeling tasks, seems to have been located on the third floor of the main building, and the enormous printing presses for all of the necessary Vogeler advertising material were located in the basement of the main building. Advertising material was prepared and supplied in eleven (11) different languages. The bindery, where pamphlets and almanacs, were bound and stitched after printing was located in the rear building, together with the separate chromolithography department where multicolored trade cards were designed, created, separated and boxed for shipment.

VOGELER “FAIRY STEAMBOAT” ON 1885c TRADECARD

1895c CANADIAN CHARLES A. VOGELER CO. COVER

With the advent of St. Jacobs Oil, the firm had to rapidly establish sales branches in “London, San Francisco, Toronto, Canada, Australia, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Cape Town, Africa” to meet the demand, according to a contemporary Baltimore puff book. The Vogelers even purchased a paddle wheel “fairy” steamboat to sail up and down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers painted with the name “St Jacobs Oil” solely for the purposes of advertising their product. It was a “fairy” steamboat in the sense that, while it was 65 feet long and 14 feet wide and equipped with four staterooms and a lavishly appointed dining room, it didn’t carry freight or passengers as a “real” Mississippi steamboat would, just advertising for St. Jacobs Oil to be distributed at its ports of call.

MORE ST. JAMES OIL TRADECARDS & A PAPERWEIGHT

However, even before the death of Charles A. Vogeler, the complexity of the arrangements the Vogelers made concerning certain nostrums other than St. Jacobs Oil that they also marketed caused the Vogelers to ordered a second private die proprietary stamp in the name of Vogeler, Meyer & Co. The disruption caused by Charles A. Vogeler’s sudden and early death seemed to pull the company in different directions and almost caused it to function as two separate divisions competing with one another. Vogeler, Meyer & Co. ultimately evolved into A. C. Meyer & Co. which was a large enough concern itself to cancel battleship revenues to pay the tax imposed during the Spanish-American War. Whether any of these cancelled stamps were actually placed on St. Jacobs Oil is unclear because it has suffered a reversal of fortune by then. Holcombe’s lack of completeness about A. Vogeler & Co. is most apparent when it comes to tracing the ownership of St. Jacobs Oil as it traveled from the possession of Charles A. Vogeler in the 1880s to its inconspicuously slipping into AHP in 1926. With respect to that particular product, he reported only that some years after Charles A. Vogeler’s death, it was sold to an “English syndicate” for $200,000. The true story is longer and sadder.

VOGELER, MEYER & CO.

1880c PRIVATE DIE PROPRIETARY REVENUE STAMPS ON PINK AND UNWATERMARKED PAPERS

SEALS USED TO REPLACE REVENUE STAMP AFTER TAX REPEALED

* * * * *

A. C. MEYER & CO. BATTLESHIP REVENUE CANCELS – ALL IDENTIFIED COLORS & DATES

May 1, 1899

May 1, 1899 – Black Cancel May 1, 1899 – Purple Cancel

May 1, 1899 – Unlisted Value

July 2, 1898 October 1, 1898

November 1, 1898

December 1, 1898 January 2, 1899

May 1, 1899 – Black Cancel May 1, 1899 – Purple Cancel

* * * * *

A. C. MEYER CO. CANCEL ON 1914 PROPRIETARY REVENUE ISSUE

* * * * *

1897 POSTCARD STATING NO ST. JACOBS OIL ADS DURING SUMMER

After Charles Vogeler’s death, the ownership of St. Jacob’s Oil passed to his widow, Mrs. Minnie Vogeler. Shortly thereafter, she formed a partnership with a prominent businessman, Christian DeVries, who not only shared in his brother’s department store business in downtown Baltimore, but also served as president of an important Baltimore bank. Soon she married him, relying upon him to take control of the marketing of St. Jacobs Oil, but once Charles A. Vogeler was dead, the glory days of St. Jacobs Oil quickly ended. By 1886, the “fairy ship” had been sold, and the Meyer and DeVries branches of the company were battling each other in the local court over DeVries’ marketing a cough syrup competing with a Meyer’s branch product and Meyer’s retaliating by marketing a product known as Salvation Oil in competition with St. Jacob Oil. These squabbles were papered over quickly enough, but, by 1896, the original inventor of the compound, Keller himself (of all people), while boasting in response to a trade magazine query seeking the formula for St. Jacobs Oil that it was still proprietary, was also decrying that the manufacture of St. Jacobs Oil had “passed into inexperienced hands, the principal owner being a muslin merchant [DeVries] who knew nothing of the business, the article did not sell so well and seems to have gone largely out of the market, compared with its former popularity and immense sales.” In fact, as a skein of subsequent lawsuits revealed, DeVries was a spectacularly bad businessman who destroyed both his own family’s businesses, as well as that of St. Jacob Oil.

1910c ENGLISH PROPRIETARY MEDICINE TAX STAMP FOR ST. JACOBS OIL LTD.

An English magazine reported in 1901 on the actual intricate proceedings that led Holcombe to record that St. Jacobs Oil had been purchased by an “English syndicate.” In December, 1899, it explained, the two owners of St. Jacobs Oil (unnamed in the article, but meaning Christian DeVries and his wife, the ex-Minnie Vogeler) signed in Baltimore an assignment for the benefit of creditors (meaning that they confirmed Keller’s lament by contracting under Maryland law to transfer their business to a trustee to dispose of its assets for the purpose of paying its debts). When the English creditors, who apparently held a major portion of the company’s debt, tried to enforce this assignment in English court to collect from the trustee, the court refused to accept the American assignment as an “act of bankruptcy within English law.” After the English creditors appealed to the House of Lords, which would not disturb this ruling of the lower court, they then made an attempt in same court to seize directly the assets of the company as payment for their debts. They were again frustrated because this time that court ruled that it did recognize the American assignment as a binding legal contract transferring title of all the company’s assets to the American trustee, leaving nothing for the English creditors to seize. The Baltimore attorney whom the trustee had dispatched as his agent to England to stave off the English creditors then apparently turned around and sold the entire business to the manager of the Vogelers’ English office (producing Holcombe’s reported $200,000). After summarizing all these facts, the English magazine article commented on the brazen solicitation of the public by the new owner to raise fresh capital:

… it does appear, according to the statement of the promoter, who has been the manager for seventeen years, that the business is an exceeding lucrative one and there are comparatively few bad debts. If the … statements are true how is it the business has collapsed, and what guarantee is there that under the same management it may not suffer a second reverse and have again to keep its creditors at bay? We should recommend to leave the company severely alone.

1902 ST. JACOBS OIL LTD. COVER

1910 ST. JACOBS OIL LTD. TRADE AD

Subsequently, from 1901 to 1913, the new company, St. Jacobs Oil, Ltd., maintained an office and a manager in Baltimore, even though organized as an English company and apparently owned by the former English branch office manager. From 1914 through 1922, the company listed Cincinnati, OH as its address in a trade publication directory of products, although by 1919 it also listed an office in the New York City business directory at John F. Murray’s ad agency, and showed the corporate officers to be Stanley P. Jadwin, president and John F. Murray, secretary, with Jadwin and Murray also listed as the directors. At least part of that time, according to that trade publication directory, its president at the Cincinnati address was one A. J. Walber, who was, coincidently, also listed as president of both the Walter Luther Dodge Co. in Cincinnati and, in the Cincinnati city directory, of Pape, Thompson & Pape. By 1923, the company’s office was safely ensconced in New York City ready to become part of AHP. To cinch the association with the AHP crowd even more tightly, in the 1922 trade publication product directory, St. Jacobs Oil, Ltd. is co-listed with the Walter Luther Dodge Co. as a proprietor of Tiz.

1922 TRADE ADS SHOWING LATER AHP COMPANIES AS PART OF ONE AD

The consolidation of all these companies took place in 1926, perhaps on the very day that AHP first opened its doors for business, but AHP was just getting warmed up. Within the next several years at least as many companies again were added to AHP. By 1928, Sterling and AHP were both swept into an even larger consolidation, with still more companies added both to AHP itself and to the larger entity. Finally, in 1931, AHP swallowed one more major pharmaceutical company, John Wyeth & Brother, so central to its existence and lasting legacy that AHP ultimately changed its name to Wyeth. All these events will be chronicled in subsequent chapters of this series.

x——————-x

¹ Yet another canceller of proprietary medicine stamps (of the 1914 series) who will get his own column someday.

² Orlando’s younger brothers, who themselves mostly trained as pharmacists, sometimes worked for O. H. Jadwin & Son in New York City, but remained settled in northeastern Pennsylvania near Scranton. Stanley’s uncle, Cornelius (1834-1913) was a leading businessman in the region, as well as being elected as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives. His pharmaceutical business, C. C. Jadwin & Co., pedaled its own patent medicine – Jadwin’s Subduing Liniment – sometimes jointly with O. H. Jadwin & Sons even after that company became part of AHP – although neither Sterling nor AHP ever listed that remedy among its own products.